Coccidia are microscopic parasites known as protozoa.

These develop in the intestinal tract of sheep and goats, and produce oocysts that pass in the dung onto the pasture where they take several days to develop ('sporulate'), after which time they can infect grazing stock.

Several species of Eimeria affect sheep and goats. These parasites are usually acquired in the first few months of life and small numbers are carried by most young animals, usually causing no ill-effects. However, with stress and overcrowding, particularly under damp unhygienic conditions, disease may occur. It is most commonly seen in young stock just before weaning, or in lambs or kids, or hoggets in feedlots, and other situations where stock are confined at very high stocking rates. Coccidiosis in young animals is usually associated with very cold conditions and poor pasture nutrition resulting in a reduced milk supply from the ewe or doe, and forcing the lambs or kids to graze close to the ground.

Sheep rapidly develop strong and lifetime immunity to coccidia, so coccidiosis is uncommon in adult animals. However, goats do not develop such a strong immunity and infection is commonly seen in goats of all ages.

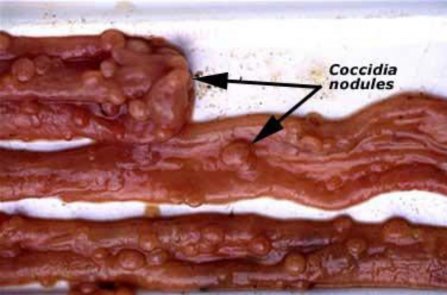

Affected animals scour (brown, liquid and foul smelling), have characteristic hollow flanks and hunched appearance, and are depressed. Deaths occur in severe cases. Although the organisms are microscopic, aggregations of some species of Eimeria may cause white nodules in the gut of affected hosts.

Most sheep and goats are infected with coccidia in the first few weeks to months of life without showing signs of infection. The disease, coccidiosis, is usually suspected when severe scouring is seen in lambs or kids at a younger age than usual for worm problems, or in sheep or goats in situations of very high stocking rates and often under nutritional stress. Affected stock fail to respond to drenching (unless significant worm burdens are also present).

Laboratory diagnosis is not definitive, as there is little relationship between the number of coccidial oocysts present in the faecal sample, and the occurrence and severity of disease. Large numbers (100,000 oocysts/gram faeces) of oocysts may be found in unaffected animals, and alternatively, disease may occur in animals with few oocysts in the faeces.

The great majority of affected animals recover without help, although some may suffer severe weight loss and some may die. Treatment of affected individuals is not usually undertaken on a mob or herd basis and registered treatments must be obtained from a veterinarian. Effective prevention can be provided by pre-treatment or in-feed products, but is only justified where there is an on-going history of disease. Attention to hygiene (feedlots) and nutrition is a more sustainable approach.

There has been some research done on the role of condensed tannins in preventing coccidiosis in goats with promising results. Kids fed Sericea lespedeza pellets had very significant reductions in oocysts per gram of faeces compared to controls. Both condensed tannins and Sericea lespedeza also help control strongyle worms in goats.

The role of other common microscopic water-borne protozoans, such as Cryptosporidium and Giardia, has only recently been investigated in Australia. It appears that infection with these organisms are relatively common in sheep and goats, but scouring as a consequence is far less common than for coccidiosis, and occurs mostly in animals up to a week old resulting in a reduction in body weights.

In goat kids, particularly neonates (in their first two weeks), but up until weaning, ‘crypto’ can cause a severe infectious gastroenteritis, especially if they are housed under moist unsanitary conditions or are artificially reared.

Of concern regarding these parasites is the potential for human infection. However, this is a relatively minor risk, as only some species of Cryptosporidium or Giardia carried by sheep or goats appear to infect humans, and by far the majority of cases in people are due to between-person contact.

The diagnosis of disease due to Cryptosporidium and Giardia is based on testing a faecal sample, but using a test different from the worm egg count. It seems that these parasites are not likely to be significant causes of scouring in sheep or goats in Australia, and treatment or prevention is not considered necessary. Access of kids and lambs under 30 days of age to adequate quantities of colostrum will help to prevent them from acquiring the infection in early life.

Crytosporidium oocyst excretion increases in the week before and after lambing in ewes, or kidding in does.

Both conditions are potentially zoonotic and Cryptosporidium outbreaks in children have been associated with patting lambs and kids. Only a few antimicrobial agents have shown activity against Cryptosporidium infection in man or animals.