Black scour worms occur in all sheep and goat production districts of Australia. Trichostrongylus colubriformis and Trichostrongylus vitrinus are the main species causing disease. T. rugatus is more commonly seen in arid regions while T. axei is not often seen. These worms are often also called “trichs” (pronounced: trikes).

Generally, T. colubriformis occurs in the warmer summer rainfall areas while T. vitrinus occurs more frequently in winter rainfall areas.

T. vitrinus is considerably more pathogenic than T. colubriformis, meaning that sheep or goats need to be treated at lower egg counts.

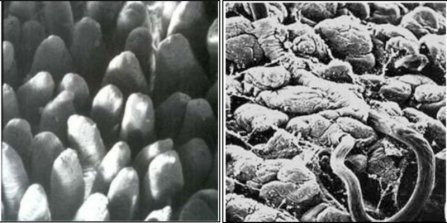

All scour worms are small, hair-like worms tapered at one end. Males are 4–6 mm long and the females are 5–7 mm long, and not easily seen at post mortem. T. axei inhabits the abomasum while the other black scour worms live in the first three metres of the small intestine of the sheep or goat where they cause damage to the lining of the gut resulting in nutritional disturbances. The adult female in the small intestine typically lays 100–200 eggs per day that are passed out in the dung.

Further ecological information on worms and their control:

Small intestine (first 3 metres) except for T.axei which inhabits the abomasum.

Death, lethargy and collapse, weight loss, damage and inflammation of the gut resulting in diarrhoea (scouring), hypersensitivity of the gut resulting in diarrhoea (scouring).

The only accurate way to diagnose worm infections before productivity losses have occurred is to conduct a WormTest (worm egg count). Also request a larval culture if you suspect a barber’s pole infestation. The results allow you to make the best choice of drench for the situation.

Visual signs of infection only occur after significant production loss has already occurred. Also, these signs can occur with other parasites and diseases.

There are many options to treat for this worm and your choice will depend on:

Your decision can be assisted by using the Drench Decision Guide a simple tool that considers some of the points above.

You can also review the Drench pages on this site to find out specific information about drenches, including their drench active, drench group, length of protection, which worms they treat, dose rate, withholding period, export slaughter interval and manufacturer.

Note: only a few drench types are registered for use in goats.

The negative impact of this worm can also be reduced through browsing and grazing management strategies and by using one of the integrated worm control programs that have been developed for different regions across Australia.